Mumbai: Scientists at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Bombay have discovered a simple and efficient method to use light to control quantum states within ultra-thin materials, a breakthrough that could pave the way for much faster and more energy-efficient computers than current electronic devices.

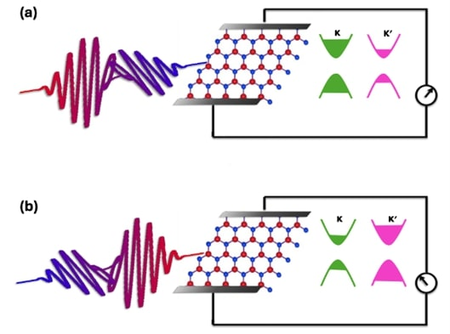

The research focuses on two-dimensional semiconductors—materials that are only one atom thick and thousands of times thinner than a human hair. In these materials, electrons can occupy two distinct quantum states known as valleys, labelled K and K′.

These valley states are analogous to the binary 0 and 1 used in conventional digital computing and form the foundation of an emerging field called valleytronics.

Until now, manipulating these valley states has been challenging. Existing methods relied on complex laser systems using circularly polarised light and multiple laser pulses. Even with such setups, control was often partial and difficult to detect, making reliable and reversible switching between valley states a major obstacle.

In a study published in the journal *Advanced Optical Materials*, the IIT Bombay team demonstrated that such complexity is unnecessary. The researchers showed that a single linearly polarised laser pulse can both control and read the valley state of electrons.

The key innovation lies in introducing a small, controlled skew in the laser pulse’s polarisation. According to Prof. Gopal Dixit of IIT Bombay, this slight asymmetry is sufficient to drive electrons into either the K or K′ valley. Reversing the skew allows the electrons to switch back, making the process fully reversible, with the two valley states effectively functioning as quantum equivalents of 0 and 1.

Adding to the significance of the discovery, the same laser pulse also generates a minute electric current. This current serves as an inbuilt signal indicating which valley state the electrons have entered. As a result, the system enables simultaneous control and readout without requiring additional lasers or external measurement devices.

The researchers further found that the technique works across a broad range of laser wavelengths and does not require precise tuning to the material’s energy levels, making it highly versatile and practical for future applications.

— With inputs from IANS