New Delhi: The publication of the Election Commission’s draft electoral roll under the ongoing Special Intensive Revision (SIR) in West Bengal has significantly weakened sweeping political claims made by both the ruling Trinamool Congress and the opposition Bharatiya Janata Party regarding large-scale voter irregularities.

The Trinamool Congress recently accused the BJP of misleading voters by alleging the presence of over one crore illegal electors in the state. However, Trinamool leaders themselves had earlier contributed to a climate of fear and uncertainty around the SIR process, with statements suggesting mass disenfranchisement—claims that reportedly even led to suicides.

While BJP leaders such as Leader of Opposition Suvendu Adhikari and Union Minister of State Shantanu Thakur had cited figures running into crores, Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee had also alleged that nearly two crore voters could be struck off the rolls. She had linked the SIR exercise to the National Register of Citizens (NRC), warning of possible detention camps and widespread exclusion.

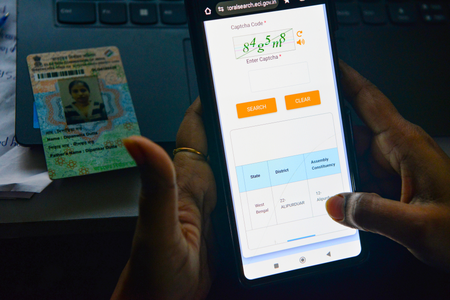

Contrary to these assertions, the draft electoral roll identifies approximately 1.8 lakh “fake” or “ghost” voters. Overall, around 58 lakh names have been marked for removal, a figure that does not substantiate claims of one crore or more voters being disenfranchised. Hearings for affected voters are expected to begin shortly, with the final electoral roll scheduled for publication on February 14.

The draft figures reveal that political narratives around the alleged presence of “one crore Rohingyas or Bangladeshis” on voter lists are not supported by the data, which is far lower than claimed. Nevertheless, political parties continue to use the draft roll selectively to advance their positions, with the BJP stating that it will offer a detailed response after the final rolls are released.

As in Bihar, political discourse in West Bengal has often mixed broader migration and demographic arguments with electoral claims. However, the Election Commission’s SIR process relies on field verification and legally defined deletion categories such as death, migration, duplication and non-response.

Importantly, the draft rolls remain provisional. Many flagged entries will undergo hearings and may either be restored or permanently removed only after due process.

Geographically, the draft roll indicates higher concentrations of flagged cases in border areas of North 24 Parganas, Matua-dominated constituencies, and select seats with significant Muslim populations. Critics of the SIR had initially focused on Muslim-majority areas, but the draft data shows that deletion rates there are relatively low, averaging around 0.6 per cent in several constituencies.

In contrast, several Matua-majority pockets record the highest deletion rates, averaging close to nine per cent in some areas. A large number of entries marked as “unmapped” or deleted are concentrated in these regions, raising concerns about short-term anxiety linked to documentation requirements, hearings and procedural delays.

The Matua community, a large and politically influential Scheduled Caste group primarily based in North 24 Parganas, Nadia and nearby districts, traces its roots to 19th and early 20th century reform movements. Many members migrated from present-day Bangladesh during and after Partition, often fleeing religious persecution. Their size, cohesion and concentrated presence have made them a key factor in West Bengal politics.

The BJP’s state unit has raised concerns with the Election Commission on behalf of the Matua community. In a letter sent to the poll body last month, the party noted that Matua members and other Hindu migrants were expressing dissatisfaction due to a lack of clarity regarding documentation requirements under the SIR process.

Overall, the draft electoral roll has punctured exaggerated political narratives from multiple sides, underscoring the gap between rhetoric and the provisional data emerging from the Election Commission’s verification exercise.

With inputs from IANS